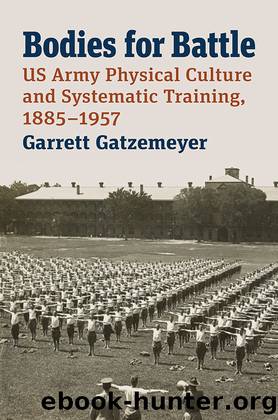

Bodies for Battle by Garrett Gatzemeyer

Author:Garrett Gatzemeyer [Garrett Gatzemeyer]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University Press of Kansas

Published: 2021-09-07T00:00:00+00:00

chapter six

hard bodies for a cold war

conditioning and prehabilitation, 1945â1957

The Cold Warâs advent brought with it an abundance of reasons for sustained interest in the bodies of the United Statesâ youth, uniformed or otherwise. At first blush, the awesome destructive power of nuclear weaponry might have implied the irrelevance of the individual soldierâs strength and endurance. Every serviceâs pursuit of high-tech weapons, advanced platforms, and space-age gadgets may likewise have suggested the soldierâs diminishing relevance. However, the Armyâs senior leaders did not forget the flesh-and-blood sinews of warfare. Warfighting concepts, revised doctrine, and new force structures, such as the Pentomic Division, consistently emphasized the necessity of fitness on nuclear battlefields. There, success was thought to depend upon dispersion and rapid, aggressive maneuver. Actual combat experience on Koreaâs battlefields also reinforced the importance of physical fitness. At the same time, the Korean War seemed to reveal the modern American manâs shortcomings once again. Other national fitness red flags, such as the Kraus-Weber report, published in 1955, also appeared to expose an emergent âmuscle gapâ with the Soviet Union and the pernicious effects of easy living in a mass-consumer society. Because the Armyâs manpower policies relied heavily on conscription, soft citizens meant soft soldiers. Youth and soldier physical training alike thus remained subjects of public and expert interest.

Throughout this period of turbulence, the Armyâs physical culture remained consistent. Cultural inertia and institutional continuity minimized change, generally restraining it to the trajectory set between 1942 and 1945. Writing in 1957, Gen. Maxwell Taylor, the Armyâs chief of staff and a principal promoter of technology-centric modernization, illustrated the endurance of cultural values and beliefs: âIt is a military duty for all officers and men to maintain a high level of physical fitness . . . to perform [their] duties with maximum efficiency,â he wrote, and then claimed that fitness inspired confidence in subordinates and fellow citizens alike by âpresenting the model of an alert, ready fighting man.â1 Taylor conceived of fitness in physical terms and as an external manifestation of intangible inner qualities. He also prioritized the average soldierâs fitness, not the âdevelopment of muscle men or record-breaking athletes,â while emphasizing the individual before the unit.2 Taylorâs definition of fitness, valuation of exercise, and focus on the individual all aligned with the Armyâs World War IIâera physical culture despite a decade of technological, doctrinal, structural, and political ferment throughout the service. Institutional continuity complemented cultural endurance in minimizing change. Although responsibility for physical training research and doctrine development changed hands several times between 1945 and 1954, ongoing studies sponsored by Army Field Forces and the US Army Infantry Schoolâs influence kept the physical culture oriented toward basic preparation for infantry combat and responsive to data-driven research. When concerns about soldier fitness arose, cultural inertia and institutional continuity encouraged a doubling-down on the existing physical culture instead of substantial revision.

Much more change occurred in the US governmentâs approach to prehabilitation. The militaryâs continuing reliance upon conscription to fill its ranks fixed attention on young, male American bodies.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Automotive | Engineering |

| Transportation |

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4283)

Never by Ken Follett(3922)

Urban Outlaw by Magnus Walker(3381)

OPNsense Beginner to Professional by Julio Cesar Bueno de Camargo(3275)

Sapiens and Homo Deus by Yuval Noah Harari(3053)

Will by Will Smith(2891)

A Short History of Nearly Everything by Bryson Bill(2678)

Hooked: A Dark, Contemporary Romance (Never After Series) by Emily McIntire(2538)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2344)

Borders by unknow(2298)

The Becoming by Nora Roberts(2179)

Holy Bible (NIV) by Zondervan(2108)

HBR's 10 Must Reads 2022 by Harvard Business Review(1828)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1827)

The One Percenter Encyclopedia by Bill Hayes(1817)

Freedom by Sonny Barger(1791)

Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone by Diana Gabaldon(1743)

Five Ways to Fall by K.A. Tucker(1730)

Girls Auto Clinic Glove Box Guide by Patrice Banks(1718)